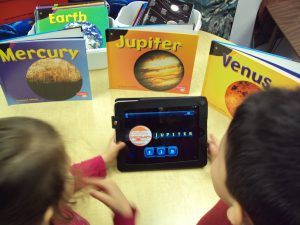

In the E-book chapter, The effects of interactive multimedia iPad E-books on preschoolers’ literacy, Strasser & Estevez-Menendez’s study (2015) demonstrates how the use of iPad e-books positively effect students story comprehension, engagement and understanding of vocabulary. Their study examined 2 preschool groups over a 6-week period, one using iPads and one completing the same tasks with paper-based books. Twice a week, students in the control group listened to their teacher read out loud the print book while the iPad group was introduced to corresponding multimedia versions of the book through the iPad. The story was narrated by the app instead of by the teacher. The teacher also demonstrated how app features worked, for example, how touching an object produced the written and spoken name of the object. For data collection and analysis, three types of instruments were designed and the following data were collected: 1) weekly vocabulary assessment tool, 2) weekly story comprehension assessment tools, 3) check list to assess the frequency of observations as well as further, unstructured observations were made throughout the study (Strasser & Estevez-Menendez’s, 2015).

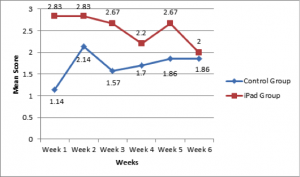

Figure 1. Weekly mean scores of vocabulary assessments by group

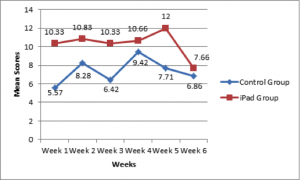

Figure 2. Weekly mean scores for the story comprehension assessments by group

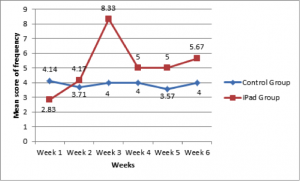

Figure 5. Weekly mean scores of frequency of engagement by group

Through the data it is clear to see that students’ vocabulary, comprehension and engagement was higher in the iPad group when compared to the control group (paper based books). However, I believe that most teachers (myself included) would never just do a ‘dry read through’ of a book and then asses children’s understandings of it. I would provide various activities to help reinforce the concept of the book including using manipulatives, for example, using story workshop for students to practice/play with new vocabulary and their retelling of the story. I think that this may be a limitation of the study because I don’t think it is very realistic to expect students to have a high understanding of a story after 1 read through. I wonder if there were discussions in the control book group and/or if they did any other activities before the assessments. It is clear that the iPad group got to interact with the story more and play with the different features to help them understand the story better.

Strasser & Estevez-Menendez, (2015) also cited research that outlines the potential limitations of touch screen technology:

“Moody and McKenna (2009) asserted that the enhanced interactivity and “edutainment” features provided by e-books became a distraction for young learners in their study, which actually hindered the learning process. In Shamir, Korat and Fellah’s study (2010), the researchers deter- mined that exposure to e-books was beneficial for students’ improvement in vocabulary acquisition and phonological awareness, but only for at risk children with learning disabilities. Moody (2010) also concluded that the use of e-books for sup- porting young children was beneficial, but that the quality of e-books determined this effect. In other words, the use of high quality interactive e- books may support emergent literacy development through scaffolding, while lower quality e-books may be more likely to include distracting anima- tions and sounds unrelated to the story”

Strasser & Estevez-Menendez (2015) consider some of this in their discussion recommendations as they outline the importance of selecting high quality e-books as well as a recommendation for educators to become familiar with the capabilities of the iPad and utilize the Guided Access controls. This allows students to remain focused without accidentally entering other areas of the app intended for adults. In connection to my practice-oriented post this week, here is some more information on Guided Access:

In conclusion it was interesting to read more information about how iPads can help support literacy in the classroom, as I will be receiving 4 iPads in the near future to be utilized in the afternoons. I will now finish this post with a final quote from the article that resonates with me:

As cited by Strasser & Estevez-Menendez (2015, p. 140) “Although most early childhood experts acknowledge that nothing can replace hands-on activities embedded in real experiences, the use of these devices is offering young children “valuable, authentic learning experiences that supplement traditional developmentally appropriate practice (Geist, 2014, p. 59)”.

References

An, H., Strasser, J., & Estevez-Menendez, M. (2015). The effects of interactive multimedia iPad E-books on preschoolers’ literacy

Recent Comments